Yesterday I attended Keith Braithwaite’s workshop titled TDD as if you meant it at the Software Craftsmanship 2009 conference, and I found it truly thought provoking. At the start of the workshop I thought that the exercise is plain silly but I publicly take it back: Keith – you really taught me something yesterday and I thank you for that.

Attendees were split into pairs who were working on the task together, using TDD practices with very strict rules:

- write exactly ONE failing test

- make the test from (1) pass by first writing implementation code IN THE TEST

- create a new implementation method/function by:

- doing extract method on implementation code created as per (2), or

- moving implementation code as per (2) into an existing implementation method

- only ever create new methods IN THE TEST CLASS

- only ever create implementation classes to provide a destination for extracting a method created as per (4).

- populate implementation classes by doing move method from a test class into them

- refactor as required

- go to (1)

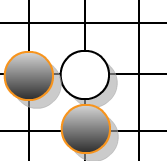

The exercise involved writing a piece of code to evaluate whether a stone in the Go game can be taken or not. The definition of whether a stone can be taken was given as it having only one ‘liberty’, with liberties defined as free horizontal or vertical places adjacent to the stone. For example, the white stone in the picture below has two liberties (diagonals don’t count) and it cannot be taken.

The picture above was the first example we had to implement. The rules were designed to strictly let the domain code evolve from the test code in baby steps, which I though was the way I’m doing unit testing anyway, so it did not feel challenging at all. My first attempt started like this:

[Test]

public void StoneHasTwoLibertiesIfTwoCornersAreCovered()

{

GoGrid grid=new GoGrid(3,3);

grid.Place(1,1,Piece.WHITE);

Keith came over and said “Wow! Where did that GoGrid come from?” The rules of the workshop were that we had to let domain code evolve from the test code, and I tried to explain that the class doesn’t yet exist and I’m using the test to drive it’s design, so in my mind I was following the rules of the game but Keith was having none of it, so we had to delete that and start over. As we weren’t allowed to use domain classes, even presumed domain classes, my next attempt was to store it in a char array and then possibly later move that out:

[Test]

public void StoneHasTwoLibertiesIfTwoCornersAreCovered()

{

char grid[][]=new char[][]{

new char[]{' ', ' ', ' '},

new char[]{'B', 'W', ' '},

new char[]{' ', 'B', ' '},

}

int liberties=0;

for (int x=0; x<3; x++)

//

Keith came over again and complained against that. At this point, I was a bit lost. I guess that my pair partner was lost as well. Keith kept asking why we were writing this code, I was explaining that I was describing the example that he gave but again he was not accepting it. Then we came to the point of what exactly we were testing and I said “well the test name says it – if the stone has two corners covered, its liberty is 2”, and Keith asked why haven’t we specified that in the test rather than starting with a grid. So we changed the test to this:

[Test]

public void StoneHasTwoLibertiesIfTwoCornersAreCovered()

{

int cornersCovered=2;

int liberties=4- cornersCovered;

Assert.AreEqual(2,liberties)

}

Finally he seemed happy with this, but to me it looked plain silly. It was not any closer to the end goal and I was just testing subtraction. Encouraging us to stick with it for a while, Keith left to help others and we continued writing other examples. After a couple more similar cases implemented as tests, we were allowed to refactor and move the code to calculate liberties to a new method in the test class. Then we started implementing cases with groups of stones, and things sort of fell into place.

Operations on groups of stones would be a lot more complicated to handle with the grid directly. The exercise was pushing us towards a design that treated groups as a whole rather than individual pieces and not having the grid as a matrix of stones defined at all. Of course the same functionality can be implemented directly on a grid but it would mean much more code and it would be much more complex.

The exercise was very interesting, although I initially thought that it is silly and too simplistic. It showed me how much hidden assumptions can affect my work if I don’t really try to express them and of course I fell into the classic trap of restating the problem and solving the restated problem first. I was thinking about something that I’ll probably need in the future and jumping too much ahead instead of just focusing on the task that I really was supposed to solve.

My counter-argument is that in real projects, not in workshop labs, I would typically have a bigger chunk of requirements and domain explored and we would try out a few designs to see which one fits the problem space best before we started coding, so unit tests will be used to flesh out the APIs but the design ideas would probably be there in some form. Nevertheless, I think that it would be really interesting to try this technique out on a real project as well. According to Keith after the exercise, classes developed like this tend to have very little or no state, very little code and end up with methods with long parameter lists, coming much closer to the functional programming paradigm. The code ends up with lots of small classes.

Read about the follow-up on this exercise as well: TDD as if you meant it: revisited