Effective prioritisation is key to delivering value with a software project. The MoSCoW model, splitting features into Must have, Should have, Could have and Would like (really Won’t have), theoretically does the trick. However, I found it very hard to apply in practice – too many things end up in the Must category. I recently came across an alternative model that seems to solve that problem.

The MoSCow model, at least when I tried to implement it, suffered from the Priority 1 Paradox:

The more we ask customers to narrow down priority 1 features the more they’ll be scared to leave anything out of that category.

The complaint is always the same: everything must be there - especially all the old functionality when replacing a legacy system. Prioritising so that most of the stuff ends up as ‘Must’ pretty much defeats the point of the exercise.

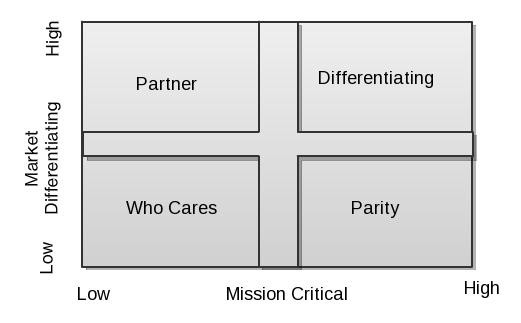

I am currently reading Stand Back and Deliver: Accelerating Business Agility by Niel Nickolaisen and colleagues from Accelinova. Among other interesting ideas, I found a real gem. This book advises aligning business processes (equally applicable to software features) along two axes: mission critical and market differentiation. Nickolaisens calls this the Purpose Alignment Model:

In a case study, the authors describe a discussion with a stakeholder who claimed that their IP protection was a differentiating factor. The authors then asked the VP of sales ‘When was the last time you sealed a deal by touting Lifebrands’ excellence in IP protection? When was the last time you felt you should include the IP protection process in sales presentations and collateral?’ (pp 36) They also offer a simpler version of this rule of thumb as a Billboard filter:

Would you put this feature on a billboard?

If so, the feature is obviously differentiating and should be invested in. If not, this feature falls into the parity category at best. The introduction of the parity category which, as the authors repeatedly point out, holds mission-critical features which are not billboard material, seems as a great way to avoid the Priority 1 paradox. This is to intentionally avoid the feeling that anything not Priority 1 won’t be delivered. The system must have these things too offer a full service, but it just isn’t worth investing too much or being too creative there. Nickolaisen and co-authors suggest that the Parity category is where companies should apply industry best practices and streamline processing.

Overdoing it in this category might actually be damaging to the bottom line. In another case study, the authors describe a project to automate complicated pricing rules. After it was identified that complex pricing isn’t really billboard material, the project was completely turned on its head. Instead of implementing a complex rule engine, the pricing system was streamlined using industry best practices. It turned out that customers were actually happier with the new model, so simplifying a parity process increased the revenue. This was possible because the stakeholders agreed that while the company must have an automated pricing system, it wasn’t a core differentiating factor.

Strategic design ideas of Eric Evans also suggest some good guidelines what to do with such software: if the thing is available off the shelf (generic domains), buy it. If not, possibly get a third party to develop and maintain it. Evans calls these domains supporting, and they are prime candidates for outsourcing.