In The Logical Thinking Process, H. William Dettmer talks about three different areas of systems:

- The Zone of control (or span of control) includes all those things in a system that we can change on our own.

- The Sphere of influence includes activities that we can impact to some degree, but can’t exercise full control over.

- The External environment includes the elements over which we have no influence.

These three system areas, and the boundaries between them, provide a very useful perspective on what a delivery team can hope to achieve with user stories. Evaluating which system area a user story falls into is an excellent way to quickly spot ideas that require significant refinement.

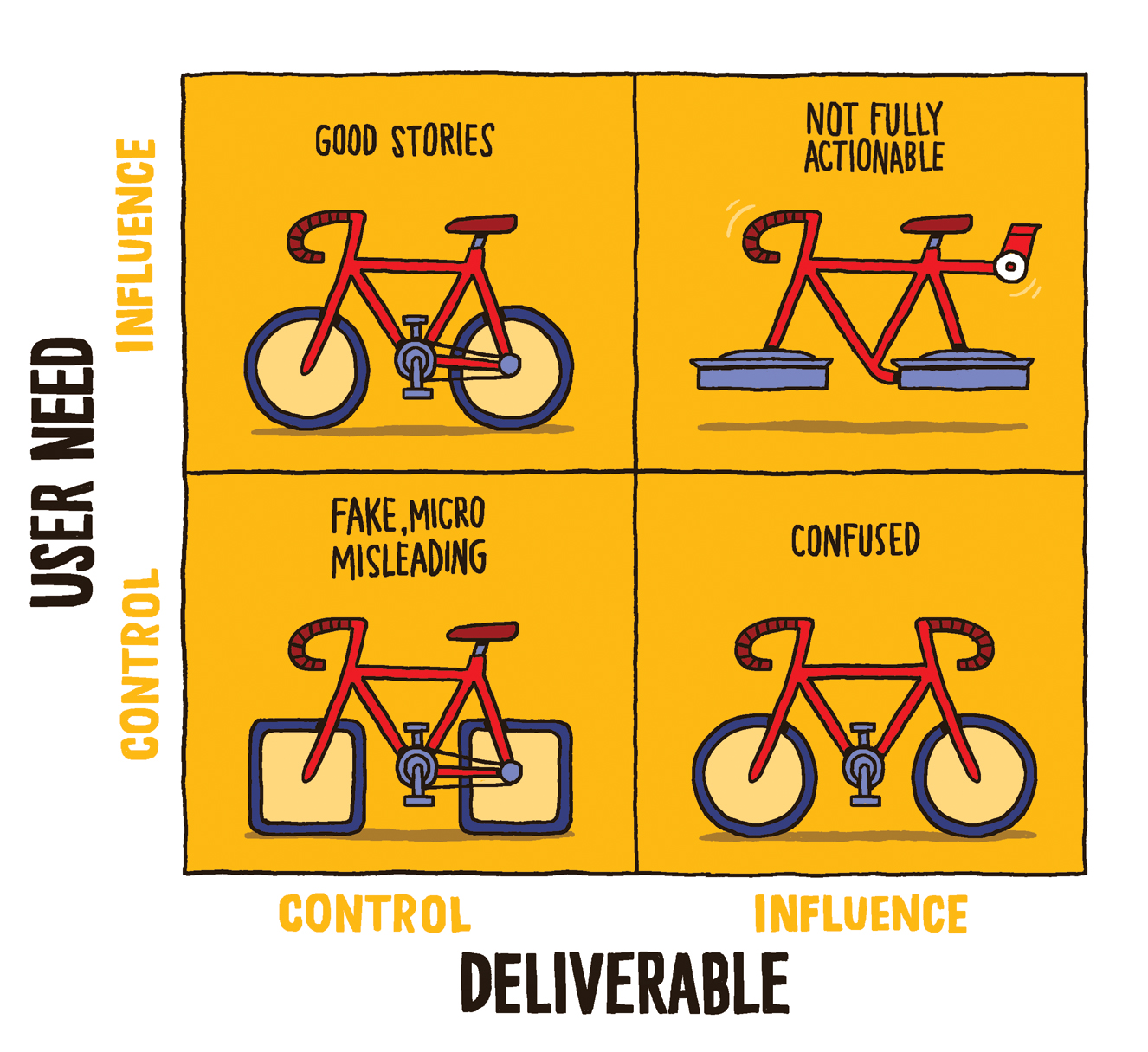

A good guideline is that the user need of a story (‘In order to…’) should ideally be in the sphere of influence of the delivery team, and the deliverable (‘I want…’) should ideally be in their zone of control. This is not a 100% rule and there are valid exceptions, but if a story does not fit into this pattern it should be investigated - often it won’t describe a real user need and rephrasing can help us identify root causes of problems and work on them, instead of just dealing with the symptoms.

When the user need of a story is in the zone of control of the delivery group, the story is effectively a task without risk, which should raise alarm bells. There are three common scenarios: The story might be fake, micro-story or misleading.

Micro-stories are what you get when a large business story is broken down into very small pieces, so that some small parts no longer carry any risk - they are effectively stepping stones to something larger. Such stories are OK, but it’s important to track the whole hierarchy and measure the success of the micro-stories based on the success of the larger piece. If the combination of all those smaller pieces still fails to achieve the business objective, it might be worth taking the whole hierarchy out or revisiting the larger piece. Good strategies for tracking higher level objectives are user story mapping and impact mapping.

Fake stories are those about the needs of delivery team members. For example, ‘As a QA, in order to test faster, I want the database server restarts to be automated’. This isn’t really about delivering value to users, but a task that someone on the team needs, and such stories are often put into product backlogs because of misguided product owners who want to micromanage. For ideas on how to deal with these stories, see the chapter Don’t push everything into stories in the Fifty Quick Ideas To Improve Your User Stories.

Misleading stories describe a solution and not the real user need. One case we came across recently was ‘As a back-office operator, in order to run reports faster, I want the customer reporting database queries to be optimised’. At first glance, this seemed like a nice user story - it even included a potentially measurable change in someone’s behaviour. However, the speed of report execution is pretty much in the zone of control of the delivery team, which prompted us to investigate further. We discovered that the operator asking for the change was looking for discrepancies in customer information. He ran several different reports just to compare them manually. Because of the volume of data and the systems involved, he had to wait around for 20 to 30 minutes for the reports, and then spend another 10 to 20 minutes loading the different files into Excel and comparing them. We could probably have decreased the time needed for the first part of that job significantly, but the operator would still have had to spend time comparing information. Then we traced the request to something outside our zone of control. Running reports faster helped the operator to compare customer information, which helped him to identify discrepancies (still within our control potentially), and then to resolve them by calling the customers and cleaning up their data. Cleaning up customer data was outside our zone of control, we could just influence it by providing information quickly. This was a nice place to start discussing the story and its deliverables. We rephrased the story to ‘In order to resolve customer data discrepancies faster…’ and implemented a web page that quickly compared different data sources and almost instantly displayed only the differences. There was no need to run the lengthy reports, the database software was more than capable of zeroing in on the differences very quickly. The operator could then call the customers and verify the information.

When the deliverable of a story is outside the zone of control of the delivery team, there are two common situations: the expectation is completely unrealistic, or the story is not completely actionable by the delivery group. The first case is easy to deal with - just politely reject it. The second case is more interesting. Such stories might need the involvement of an external specialist, or a different part of the organisation. For example, one of our clients was a team in a large financial organisation where configuration changes to message formats had to be executed by a specialist central team. This, of course, took a lot of time and coordination. By doing the zone of control/sphere of influence triage on stories, we quickly identified those that were at risk of being delayed. The team started on them quickly, so that everything would be ready for the specialists as soon as possible.

How to make it work

The system boundaries vary depending on viewpoint, so consider them from the perspective of the delivery team.

If a story does not fit into the expected pattern, raise the alarm early and consider re-writing it. Throw out or replace fake and misleading stories. Micro-stories aren’t necessarily bad, but going so deep in detail is probably an overkill for anything apart from short-term plans. If you discover micro-stories on mid-term or long-term plans, it’s probably better to replace a whole group of related stories with one larger item.

If you discover stories that are only partially actionable by your team, consider splitting them into a part that is actionable by the delivery group, and a part that needs management intervention or coordination.

To take this approach even further, consider drawing up a Current reality tree (outside the scope of this post, but well explained in The Logical Thinking Process), which will help you further to identify the root causes of undesirable effects.